Survey Glossary & Survey Article Index

Terminology frequently used in a survey project are defined in our survey glossary. Links are provided to articles of ours discussing the terms.

Terminology frequently used in a survey project are defined in our survey glossary. Links are provided to articles of ours discussing the terms.

Summary: Why is that local companies with a loyal following falter so often when bought by an out-of-town company? In Boston in the fall of 2013 we lost Hilltop Steakhouse, an iconic landmark on the North Shore.

~ ~ ~

Growing up on the North Shore of Massachusetts meant a regular pilgrimage to Hilltop Steak House, anchored by the larger-than-life 68-foot-tall neon saguaro cactus on Route 1 in Saugus. The steaks were good, portions were very generous, prices very reasonable, the service was efficient, the drinks were strong (according to my dad), and the waiting lines were ridiculous. 2 hours of waiting with the numbered card in hand was the norm despite seating for over 1400 people.

Growing up on the North Shore of Massachusetts meant a regular pilgrimage to Hilltop Steak House, anchored by the larger-than-life 68-foot-tall neon saguaro cactus on Route 1 in Saugus. The steaks were good, portions were very generous, prices very reasonable, the service was efficient, the drinks were strong (according to my dad), and the waiting lines were ridiculous. 2 hours of waiting with the numbered card in hand was the norm despite seating for over 1400 people.

Sadly, that icon has passed, closing its doors on October 20 of last year — yet another example of a locally owned business that has fallen by the wayside after being sold a number of years ago.

We all have probably seen this story in our own neck of the woods. A local company prospers by understanding the interests, needs, and wants of the area clientele, resulting in the delivery of a high value product-service combination. The owner thought about building a business for the long term. Then, for any number of reasons the company is sold perhaps to a large corporation that may see a business that can be turned more profitable. “Those local yahoos just don’t know how to run a business…”

Investment in the product is scaled back, costs are cut, prices are raised, the value proposition falters, and customer loyalty is lost. Generally, this is a downward spiral that continues until bankruptcy, but sometimes the original owner buys back the company for pennies on the dollar and rescues the company.

With Hilltop, product quality — the steaks — went down while prices went up. Volume dropped to the point of using only 1 of 3 dining rooms in the 1400 square foot facility. With all that overhead turning a profit was as tough as the steaks. Finally, the owners threw in the towel.

You will find no greater believer in free-markets than I. So, I’m not suggesting that a company shouldn’t sell to a buyer. But the intellectually curious part of me wonders why the new owners so frequently misread what made the acquired business successful. And so frequently screw it up royally. Is it the obsessive focus on quarterly profits that comes with being a public company?

You will find no greater believer in free-markets than I. So, I’m not suggesting that a company shouldn’t sell to a buyer. But the intellectually curious part of me wonders why the new owners so frequently misread what made the acquired business successful. And so frequently screw it up royally. Is it the obsessive focus on quarterly profits that comes with being a public company?

Now, I did have a final dining experience at Hilltop the last week before closure, dining with a home-town friend. Lots of people went for a final nostalgic sirloin steak, so it was a very friendly crowd. I had a very dry martini in honor of my dad. Still strong. And I dined while watching John Lackey beat Justin Verlander 1-0 in the Red Sox drive for the World Series. Just another — but final — dinner at Hilltop that I will remember for some time…

PS: To see the imprint of Hilltop upon the area, go to eBay and run a search on Hilltop steakhouse. Our waitress gave us some extra placemats that perhaps I should list.

Summary: Are pay-to-play laws meant to protect us against kickbacks in government contracts, but are they an unwarranted attack on First Amendment freedom of speech?

While I normally stay on the topic of feedback management and related topics, I recently was forwarded an email that should concern all of you who are Americans. (No offense to my international friends, but you still may find this interesting.) And some of you no doubt will disagree with me or think my concerns are overblown.

My wife works for a large corporation, and it sent an email to all employees about the ramifications of so-called “pay-to-play” laws that many states and municipalities have adopted. To quote the key section:

These laws restrict [companies] and, in some instances, its employees and members of its Board of Directors, from making monetary and in-kind (including donated labor, materials, and services) political contributions to, or soliciting such contributions on behalf of, candidates for certain elected offices, political party committees and other political committees (e.g., PACs). Some of these laws prohibit [companies] from entering into a government contract for a certain number of years if [the company], an employee, or a member of the Board makes or solicits a “covered contribution.”

Depending on the jurisdiction, the law may even cover certain family members (such as spouses and children) of [company] employees or Board members. Violating these requirements may lead to civil and, under certain circumstances, criminal liability.

Accordingly, [the company] is requiring all employees and members of the Board of Directors to pre-clear certain personal political contributions in the jurisdictions that have “pay-to-play” laws.

The ostensible goal is to avoid kickbacks to get government contracts. In the age of Blagojevich, pay-to-play concerns are real. In my home state of Massachusetts our previous Speaker of the House is now serving time for steering state business to a company; however, no campaign contributions appear to have been involved.

One aspect of many of these laws is to make public large contributions from business leaders, which is required by law even for PACs. But these laws may intimidate some, in essence negating the Supreme Court Citizens United decision. Strong arguments can be made about whether the unintended consequences outweigh the positives.

But consider the broad scope of this crop of laws. My wife is a mid-level software engineering manager. She has no direct contact with customers and is far removed from any sales processes. Our state is not in an affected jurisdiction (yet), but what if we were. If I wanted to make a $100 donation to a candidate, make phone calls on his/her behalf, or even to hold a sign at a rally, I would have to get clearance from corporate legal.

I guess the good thing is that this legislation has spawned a new compliance industry and is creating jobs for lawyers. But at what cost?

I want to say this is absurd, despite the ostensible clean government goals, but the sweeping scope actually makes these laws chilling attacks on First Amendment freedom of speech rights. Why should I have to get approval to exercise my First Amendment rights? Imagine someone getting fired because his/her spouse attended a political rally holding signs for a candidate. Imagine the mischief that can be raised as the anti-business crowd seeks to find companies that are not in compliance.

It’s just wrong.

Regardless of political affiliation, we should all be concerned.

Want to know if you are potentially affected? Here’s the list of jurisdictions with such laws according to the email

Summary: When a company chooses to implement a CRM system, several critical questions must be addressed. How much of the company’s front-office business processes will be – or should be – changed by the system implementation? Can only selected business processes that affect a customer be augmented with automation or must all customer touch points be re-engineered? Should all processes be re-engineered simultaneously or is there a logical order to proceed – or an illogical order to avoid? This article outlines a case study where the initial approach was to isolate certain sales and marketing functions as the target for the CRM implementation. Midway through the project, the company recognized that all aspects of the customer order, fulfillment, and support processes needed to be considered even if not all would be re-engineered in the initial stages of the CRM project. They also recognized that certain front-office processes were more logical candidates for the initial re-engineering.

~ ~ ~

Abselon Corporation – not its real name – is part of the old economy. The privately held company, located in the Midwest, designs, manufactures and sells electrical components for large scale installations, such as major power stations or large office buildings. Their products have a proprietary design that has given the company a competitive advantage over the years. In the past decade, the company replaced its Manufacturing Resource Planning (MRP) system, but to get the full value of that new system, it needed better visibility downstream into the product sales channel to create better product forecasts.

These events started Abselon on its venture in the world of Customer Relationship Management (CRM). The journey is still in process, but it has not taken the path management originally thought. Abselon’s story is a classic case of an innovation process where the innovators lacked the full breadth of knowledge to execute the innovation correctly and to understand the full implications the new technologies would have upon business practice – mostly because they didn’t know what they didn’t know. Abselon’s core competency lies in electrical products, not in information technology (IT) systems, sales force automation, or customer fulfillment systems. Because the Abselon management team didn’t know the right questions to ask, they stumbled as they digested drastically different opinions from various experts about the course they should take, and in the end they adapted and took a different approach then originally intended.

This article will review the case history of Abselon’s CRM experience to date. It is not an uncommon story for an IT innovation in a company’s administrative systems. There are lessons here for any company planning to re-engineer their front-office systems to take advantage of the latest technology.

Abselon’s management followed developments in information technologies. While they did not have a strong IT department, management did keep abreast of industry news, looking for ways to improve their business practice through IT. They had in fact implemented an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system recently to replace their decades-old MRP system, and it was this system that made obvious how little knowledge they had at headquarters about the sales pipeline. The forecasts manufacturing was using proved unreliable, and for a small company with 12,000 unique products, bad production planning led to high and costly inventories.

The desire to increase control and accountability for the sales process led Abselon to purchase one of the first sales force automation (SFA) tools. It all seemed simple enough. However, this innovation failed miserably. The most glaring shortcoming was that the design of the SFA tool could not accommodate the way Abselon sold its products. Abselon has accounts, that is, its 1000 distributors, but its sales process was also organized around projects. For example, a major building complex would represent a project, and a salesperson’s focus might be to try to sell Abselon’s products to the project owners and designers. The SFA product could not implement this concept of a project in the sales process.

The second major shortcoming of the SFA tool was how it was implemented. Management made the selection, and once it was bought, management told the sales force they would be using this new tool. Further, little training was provided. Without user involvement in the selection and implementation process, the sales force felt no ownership of the changes being attempted to their work processes, and they quickly realized that the new system increased management’s ability to watch and control their work activities. Since it provided them no real benefits and impinged on their independence, few used the SFA tool. For the few who used it, the SFA innovation was a glorified contact management tool.

Still, the implementation proceeded until the Latin American subsidiary was to implement it. The vice president for Latin America, himself a former salesman, recognized the folly of the “solution.” He conducted a personal search for an outside expert to help make his argument to the rest of the management team. Through various articles in IT periodicals, he found a luminary in the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) field, who was brought on board in the Spring of 1999 to help implement a system that would meet the needs of the “front office” systems.

The consultant dove right in, conducting interviews to document the sales and marketing process. As with many industrial product companies, Abselon has developed over the years a fairly complex sales and distribution process, one with a number of different “customers” in the sales flow. The 1000 distributors are the heart of the process since they are the immediate customers. That is, they’re the ones who write checks to Abselon. The 80/20 rule applies to these distributors since about 200 of them provide a vast majority of Abselon’s sales, and there is consolidation in the ranks. The “mom and pop” distributors are slowly disappearing.

The end customers are the construction site owners who need to be influenced to specify Abselon’s products. Key influencers in the specification stage are the architects, mechanical engineers, and subcontractors on the building projects. Abselon’s salespeople in fact spend much of their time educating these influencers on why Abselon’s products represent a better value despite their higher cost. Contact with all these customer types were modeled for inclusion in the new system design.

Before going into any sales calls, it helped for the salesperson to have some background about recent account activity. Historically, the company’s structure has been decentralized, and a salesperson would call the local Customer Service person who handled the account, but online access to this information would be beneficial.

The simplest part of the front office to understand was the marketing function. It really didn’t exist. Sales was king; marketing designed literature. There was no strategic marketing or marketing research activity. Mining the sales data was not even on the horizon of future goals for the marketing department.

Once the consultant had documented the sales flow, he developed a Request for Proposal (RFP) that was sent off to a number of vendors with whom he had long-standing relationships. Several proposals were received by the turn of the year. About this time, Abselon hired a new senior vice president for sales, and included in his responsibilities was the Customer Service function. He recognized that “fixing” the sales and marketing problems would only exacerbate a new key weakness in the company: order taking and fulfillment.

In a totally separate initiative, Abselon decided for efficiency reasons to centralize the Customer Service function, which handled ordering and fulfillment. So now, the distributors and the sale people worked through people in headquarters rather than people in local offices. Not surprisingly, none of the previous customer service representatives (CSRs) relocated to headquarters to fill those roles. When those people left, so did much of Abselon’s most important knowledge: how to care for each customer.

Abselon’s order taking “system” was a loose hodgepodge of tasks that varied across the distributors. Salespeople frequently played a significant role in the order taking process for standard orders. Some distributors faxed in orders; others called them in. Some wanted a faxed confirmation; others did not. And so forth. The long-standing working relationships the distributors had with their local CSRs was a key element in the overall product-service mix Abselon delivered its customers. Rather than contempt, familiarity bred comfort and loyal customers.

There was no IT system to administer and control the customer service functions and to keep track of how every customer wanted to be handled. It was all in the heads of the CSRs, and with centralization and the consequent attrition, that knowledge was lost. The lack of familiarity now bred contempt, and Abselon was losing sales because the ordering process was being mishandled time after time.

The CRM innovation being planned, as outlined in the RFP, did nothing to improve the operations of the customer service department. Streamlining the sales process would only make matters worse in customer service. The sales vice president and the CEO demanded that the customer service function be included in the re-engineering effort. Through an industry colleague, the CRM consultant brought in another consultant whose specialty lay in customer service areas.

A battle of the experts ensued. The first consultant wanted to move ahead with the initiative in process. The second felt that the customer service processes had to be included in the scope of the CRM re-engineering. Egos and reputations were at stake. The pain in the customer service function was so great – and visible since it was now centralized in the headquarters building – that Abselon management wanted the comprehensive re-engineering. Vendors, who were about to perform demos, were told to wait for an amended RFP that would include customer service issues. Whereas sales needs were the initial drivers of this CRM project, it was now a passenger. Customer Service needs were the real driver.

A team, including members of the customer service function, performed the data collection and analysis of its functional processes. With that information, Abselon forwarded the amended RFP to a new list of CRM vendors, ones whose product scope included the customer service functions. Abselon selected three companies for more intensive review. Members of the team perform visits to reference accounts, and the three vendors performed product demos, all on the same day, at Abselon headquarters. The vendor selected was an industry leader. The criteria for the selection were a combination of many factors: functionality, professionalism of sales delivery, references, and, of course, price.

Abselon’s next key decisions were: how much to implement, in what stages, and who would do necessary customization. Abselon opted to initially implement the customer service modules to get that function fixed. Rather than engaging in major customizations from the outset, they implemented a near out-of-the-box version. This allowed the project team to gain a first-hand appreciation for the product’s capabilities before engaging in customization. The project currently stands at this point, and improvements in customer service have already been realized.

Abselon’s case history illustrates many critical lessons for a company considering a CRM innovation.

Written with Mikael Blaisdell

Those of you old enough to be invited to join AARP should recall the game show by the name of this article — one of the longest running game shows ever. The show had a panel of celebrities who would try to guess someone’s profession by asking yes or no questions. Imagine if one of your customer service employees were on the show. You might think that his or her profession would be easy to guess, but I’ll wager that the way many customer service people view their jobs would likely make their professions hard to guess.

Let me give you a couple of extreme examples.

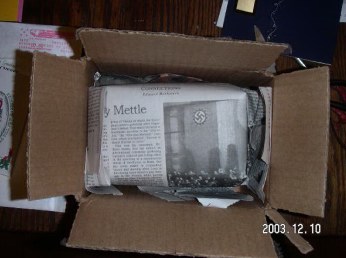

As a holiday gift from a company that provides me professional services, I received a block of 2-year-old cheddar cheese from a small cheese maker in New Hampshire — and I just crave strong cheese! When I opened the box, my jaw dropped. Look at the accompanying photo and you’ll see why. From the label on the outside of the box, I was expecting some food item, so imagine what I thought for those first few seconds. Is this Nazi cheese? Then I smiled a bit amazed at the probability that such a mistake could happen.

Someone’s job at the cheese shop was to wrap the cheese in a few sheets of newspaper, place it in the box, seal the box, place the label on the box, and ship it. Very likely, the job was defined as a strict series of discrete tasks. Was part of the job defined as ensuring the presentation of the cheese in the box was proper? I doubt it. Imagine if instead the job had been defined more simply as ensuring the gift item arrived properly at the recipient’s home or office? That is, imagine if the worker was given a broader definition — proper packaging — rather than a set of narrow tasks?

Now, in that packer’s defense, the newspaper used was the New York Times, and it was an op-ed piece that included the photo with the swastika. (Knowing the Times, you can be certain they weren’t promoting fascism.) And it was the busy holiday season, but still… I was shocked that the packer didn’t notice the swastika glaring back at him or her before folding the box closed.

Now, in that packer’s defense, the newspaper used was the New York Times, and it was an op-ed piece that included the photo with the swastika. (Knowing the Times, you can be certain they weren’t promoting fascism.) And it was the busy holiday season, but still… I was shocked that the packer didn’t notice the swastika glaring back at him or her before folding the box closed.

Contrast this with a recent experience my wife and I had at one of our favorite restaurants, Bullfinch’s in Sudbury, Mass. Close friends of ours took us there to celebrate my wife’s birthday — one of those round number ones I’d better not mention… After our meal, we were toying with what desert to order when our waitresses (we had two since one was in training) came out singing Happy Birthday carrying a lovely chocolate desert topped by a candle.

While we devoured the desert, we had an interesting conversation: “Did you tell them?” “No, I didn’t tell them. I thought you told them.” “No, are you sure you didn’t tell them when you made the reservations?” “I don’t think so…”

Turns out the waitresses heard us talking about my wife’s birthday and decided to surprise us.

How do you think Bullfinch’s defines the job of the wait staff? Do you think they have narrow task definitions — take drink orders, take meal orders, try to upsell customers with appetizers — or do you think they have a simple job definition that focuses on the desired outcome of a visit to the restaurant — make the guests’ visit as special as possible? I haven’t talked to the owner about her training philosophy, but I’ve dined there enough, especially on special occasions, to know the philosophy first-hand (or first-fork).

When you develop the job definitions within your organization and reinforce them through performance appraisals, how do you define those jobs? Are they narrowly defined on tasks the person needs to perform, prompting narrow thinking, or are they broadly defined to prompt the employee to take responsibility for the quality of the end product? Walk up to a front-line service agent and ask them what their job is — or play what’s my line and ask them if their job is <insert narrow phrasing of task execution>? If you find a narrow focus, ask them why. Most likely you’ll find that the performance appraisal metrics are driving narrow thinking.

Now ask yourself, do you think your organization is better positioned to bond customers to your company with employees who perform narrowly defined tasks or who take broad responsibility for the customer’s satisfaction? To put it another way, do you want employees who can quickly package cheese even though offensive symbols might be showing or do you want employees who will surprise a customer on her birthday?

~ ~ ~

This photo epitomizes the notion of narrow job definitions. It was sent to me with the subject line, “Not my job.”

This photo epitomizes the notion of narrow job definitions. It was sent to me with the subject line, “Not my job.”

Think about it!