Bribes, Incentives, and Video Tape (er, Response Bias)

Summary: Incentives are part of many email requests to take a survey. Recently, I saw this taken to a shocking extreme. I was blatantly offered a bribe to give high scores. This article will cover the pros and cons of incentives. Incentives are known to be a two-edged sword. But this example highlights how incentives can corrupt survey data. Are the data real or fabricated?

~ ~ ~

Ever had someone try to influence your willingness to answer some survey? Of course you have. Many, if not most, surveys come with some offer to get you to take the survey, but I recently had a truly blatant example that made my jaw drop. As I describe this “incentive,” I’ll place it within a framework that will allow you to think more deeply about the interaction between the drive for higher response rates to reduce non-participation (or non-response) bias and the potential to corrupt the data you intend to analyze. Response rates and incentives are always a vibrant discussion topic in my survey workshops.

Everybody wants higher response rates perhaps because it’s one of the easiest survey factors to understand — even in the C suite. More responses means higher statistical accuracy. So, surveyors put considerable emphasis upon improving response rates. Perhaps so much that new problems are created.

Everybody wants higher response rates perhaps because it’s one of the easiest survey factors to understand — even in the C suite. More responses means higher statistical accuracy. So, surveyors put considerable emphasis upon improving response rates. Perhaps so much that new problems are created.

In addition to better accuracy, getting a higher response rate reduces the non-participation (or non-response) bias. With a low response rate you are less sure that the data collected properly represents the feelings of the overall group of interest, i.e., your population. This bias or misrepresentation in the data set is created by those who chose to not respond. That’s why it’s called a non-response or non-participation bias. Consider elections where certain groups are less inclined to vote. That’s a participation bias.

Many factors influence response rates and thus the non-participation bias:

- Administration mode chosen: each modes affects demographic groups differently

- Quality of the survey administration process, especially the solicitation process: effectiveness of the “sales pitch,” guarantee of confidentiality, frequency of survey administrations, reminder notes, sharing of survey findings with respondents

- Quality of the survey instrument design: length, layout, ease of execution, engaging nature of the questions

- Relationship of the respondent to the survey sponsor

- Incentives

While the relationship of the respondent audience to the surveying organization is without doubt the most important driver of response rates, my focus here will be on the impact of incentives. Why? Because in driving for more responses through incentives, we may actually corrupt the survey data by introducing erroneous invalid data — a response bias.

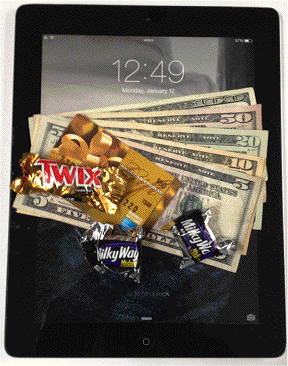

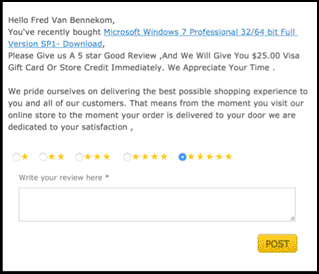

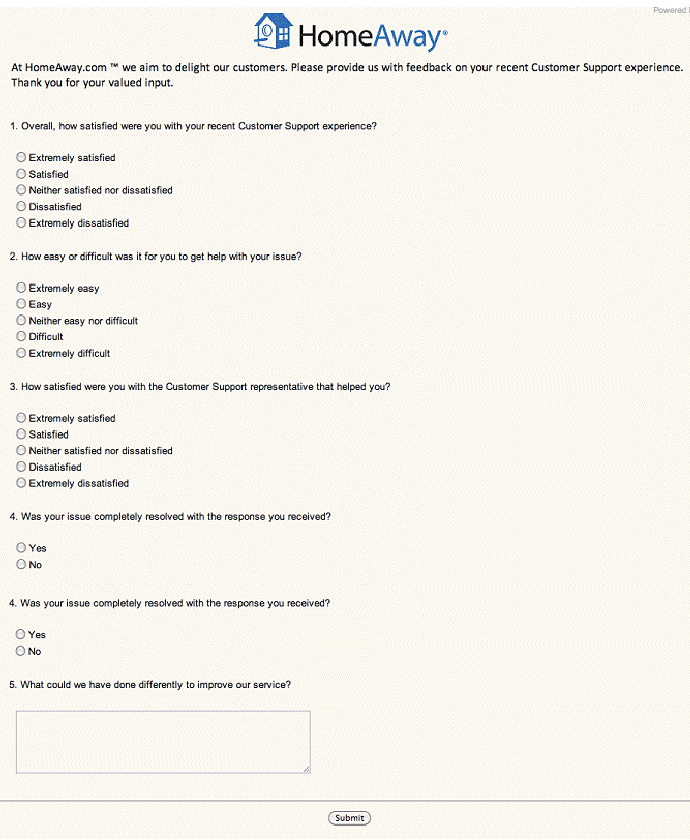

I recently bought a license from SideMicro.com for a Windows 7 license to run under Bootcamp on my new Mac laptop. The transaction was perfectly fine. Good price. Got the link to download the software. The product key worked as expected. I then got a follow up survey request by email. Here’s what it said: (See screenshot.)

Please Give us A 5 star Good Review ,And We Will Give You $25.00 Visa Gift Card Or Store Credit Immediately. We Appreciate Your Time .

Wow! Before I dissect this, let me point out a deception. Would you rather have a $25 gift card or a “store credit” — whatever that is? Cash is king. What did I get — and probably everyone else who fell for the hook? A coupon code good for 10% off additional purchases. I actually wrote to them to say that I didn’t appreciate the deception, but I got no response.

Wow! Before I dissect this, let me point out a deception. Would you rather have a $25 gift card or a “store credit” — whatever that is? Cash is king. What did I get — and probably everyone else who fell for the hook? A coupon code good for 10% off additional purchases. I actually wrote to them to say that I didn’t appreciate the deception, but I got no response.

They got what they wanted — a high score for the ratings folks. But am I now more or less loyal to them? If I bought from them again, would I comply with their request for high scores? That answer is obvious.

Lesson: The survey process itself can affect loyalty.

Now let me turn to incentives. The goal of an incentive is to motivate people to take the survey who don’t feel strongly and wouldn’t otherwise take the survey. That reduces the non-participation bias.

Incentives fall into two categories depending upon when the incentive is provided to the respondent:

- Inducements. The incentive is provided with the survey invitation. Example: a survey by postal mail with some money inside. We have no guarantee that the person will take the survey.

- Rewards. The incentive is provided after you take the survey.

For the same budget we can offer a larger reward vs. inducement.

Here’s a key question. Is the incentive motivating people to:

- Take the survey and provide legitimate, valid data? or

- Just click on response boxes to get the prize, that is, provide bogus, invalid data? (I call this monkey typing.)

An incentive should be a token of appreciation. If the incentive increases response rates reducing non-participation bias, that’s good. But if it leads to garbage data being entered in the data set — a response bias — that’s bad. More, but bad, data is not the goal! If we offer incentives in our survey programs, we all know in our hearts that some people are just monkey typing, but we want to make that minimal. I have actually counseled clients to reduce the size of their incentives for fear it would promote unacceptable levels of monkey typing.

Consider the incentives you’ve been offered to take a survey. We’ve all had service people try to influence our responses on a survey. Some are subtle and unobtrusive, for example, by actually doing their job to a high degree of excellence, which is the behavior that a feedback program should create, or politely telling us that we might get a survey about the service received and hope that you’ve had a good experience. Then there are the blatant pitches, such as the car salesperson who hands you a copy of the JD Power survey you’ll be receiving — with the “correct” answers filled in.

On a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is outrageously blatant, this pitch from SideMicro gets a 12. I have never seen such a overt bribe to get better survey scores. In an odd way, though, I respect their honesty. They weren’t coy or obsequious. They were direct. “We’ll pay you for a high score.”

Regardless of how we feel about this manipulation, the effect it creates is called a response bias. A response bias occurs where the respondents’ scoring on a survey (or other research effort) is affected by the surveying process, either the questionnaire design or the administration process. In other words, something triggers a reaction in the respondent that changes how they react to the questions and the scores they will give.

Think about the surveys you’ve taken. Did something in the solicition process or the questionnaire itself affect how you answered a question? The result is that the data collected do not properly reflect the respondents’ true views. The validity of the data set is therefore compromised, and we might draw erroneous conclusions and take incorrect action based on the data.

Response biases exist in many flavors and colors. Conformity, auspices, acquiescence, irrelevance, and concern for privacy are common types. Incentives typically create an irrelevancy response bias, but it could also create an auspices bias.

- Irrelevancy means the respondent provides meaningless data just to get the prize. You might see this in the pattern of clicks where the radio buttons are in the table to the right of the screen. You might see straight line answers — all 1s or 10s — or the famous “Christmas tree lights” diagonal pattern.

- Auspices is where the respondents gives the answer the respondent wants, which was the bias created from the payoff by SideMicro.

Lesson: A goal of the survey administration process is to generate a higher volume of valid data that reflect the views of the entire audience. Incentives are a two-edged sword. They may positively reduce the non-participation (non-response) bias, but that could be at the cost of introducing measurement error into the survey data set from bogus submissions.

That is, unless the goal of the survey program is purely for marketing hype, as is the case with SideMicro. They clearly don’t care about getting information for diagnostic purposes.

Lesson: Many survey “findings” we see from organizations are simply garbage due to flawed research processes.

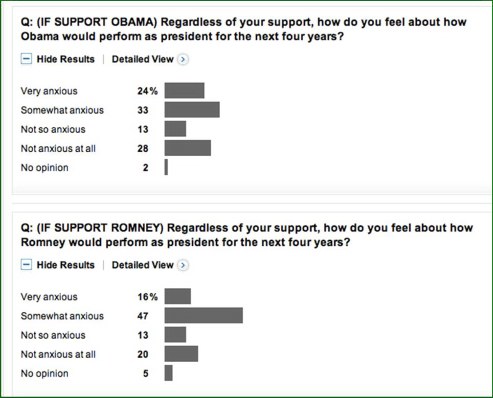

For example, let’s look at a Washington Post ABC news poll from late August, 2012. One survey question used an “anxious scale” that could easily create ambiguity. I have never seen an “anxious scale” used — and for good reason. “Anxious” can have multiple meanings. In high school, I was anxious for the school year to end but I was also anxious about final exams.

For example, let’s look at a Washington Post ABC news poll from late August, 2012. One survey question used an “anxious scale” that could easily create ambiguity. I have never seen an “anxious scale” used — and for good reason. “Anxious” can have multiple meanings. In high school, I was anxious for the school year to end but I was also anxious about final exams.

Notice I wrote, “If their complaint gets voiced.” Most people won’t bother to complain. In some cultures, people are more or less likely to voice a complaint. Regardless of the culture, most complaints will go unvoiced. Here’s where surveying — and other customer feedback channels, including social media — come into play. Part of the goal of a survey is to give voice to complaints. This is particularly true of surveying at the close of a transaction, but it also holds true for periodic surveys, such as annual surveys. The survey invitation is in essence an invitation to tell what’s wrong (if anything).

Notice I wrote, “If their complaint gets voiced.” Most people won’t bother to complain. In some cultures, people are more or less likely to voice a complaint. Regardless of the culture, most complaints will go unvoiced. Here’s where surveying — and other customer feedback channels, including social media — come into play. Part of the goal of a survey is to give voice to complaints. This is particularly true of surveying at the close of a transaction, but it also holds true for periodic surveys, such as annual surveys. The survey invitation is in essence an invitation to tell what’s wrong (if anything).