Delusions of Knowledge — The Dangers of Poorly Done Research

Imagine you’re planning to conduct a survey to support some key business decision-making process. But you have to get results fast. So, you throw together a quick survey since something is better than nothing. Right? Wrong.

Why is this wrong? Because this knee-jerk survey process may contain biases and errors that lead to incorrect and misleading data. Thus, the decisions made from this data will be based on delusions of knowledge. The purpose of this article is to outline the types of biases and errors common to survey projects. Knowledge of these will help you create a survey that provides meaningful results.

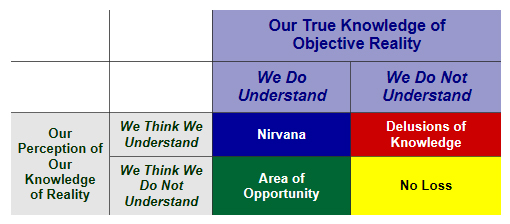

First, though, let’s drive home this issue of true knowledge versus perception. Consider the following matrix. (As a quasi-academic, it’s a requirement to present ideas in 2×2 matrices. <grin>)

In this matrix, our true understanding of objective reality – we know the truth or in fact we don’t – is contrasted to our perception of our understanding of reality – we think we know the truth or we think we don’t. Let’s look at each quadrant.

Northwest Quadrant: We think we know reality and in fact we do. This is our goal. We want to live in this cell. Nothing but blue skies do we see…

Southwest Quadrant: We think we don’t know reality but in fact we do. This is a good zone because of the opportunity it presents. We’re not going to run off half-cocked and do something stupid. We’re cautious in this position awaiting someone – a manager, a mentor, our mate – to tell us that we know more than we thought and to give ourselves more credit. In the Knowledge Management field this is known as Tacit Knowledge in contrast to Explicit Knowledge found in the NW quadrant.

Southeast Quadrant: We think we don’t know reality and in fact we don’t. This is another good zone since we’re unlikely to make wrong decisions. However, that opportunity in the previous quadrant is lacking since we lack real knowledge. Our mentor first has to help us learn, and then realize what we have learned. We want to move to the Southwest quadrant and not to the Northeast quadrant.

Northeast Quadrant: We think we know reality but in fact we don’t. This is our black hole of decision making where we’re operating under delusions of knowledge. Many versions of this exist. Maybe one customer or employee complains and the assumption is made that this is a real problem that everyone confronts. Maybe we’ve done some “research” but the research plan or execution is flawed. A whole host of reasons can create delusions of knowledge. You probably know many people who fit this quadrant: “He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

But how could a survey research project create such delusions? “A survey is so simple,” you say. “I get surveys in the mail all the time, and I’ve thrown together my own surveys. All research is beneficial. How could any survey effort not help? This isn’t brain surgery, after all.” But it is (sort of). We are trying to get into the brain of some group of interest — our customers, employees, stockholders, suppliers, etc. – and measure their perception of us and perhaps collect some other hard data.

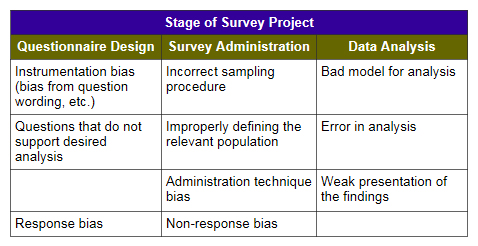

A survey project presents many, many opportunities to screw up. The following table lists the areas where biases or errors can affect our survey results – and thus our decisions.

In any research program, including surveying, the researcher faces a constant struggle to avoid introducing biases into the data and errors into the findings and conclusions. For a novice surveyor real danger exists. Why? Because the novice isn’t even aware that these biases could exist, they don’t know enough to avoid them, they won’t know they’ve created these biases, and they won’t know to take caution when interpreting the collected data set. The novice will execute the flawed project, analyze the data and draw conclusions using data that doesn’t represent the true feelings of our survey population, our group of interest.

Future articles will address each of those three major areas in depth. I’ll add links when they’re written. The bottom line message is that rigor is needed in any research project to be sure that you’re truly learning something about the area of interest.

In summary, would you rather make decisions based on:

- Sound research data, or

- Data you thought was right but was wrong or

- Gut feel and business intuition?

While I would always prefer the first choice, I’d rather operate from intuition than delusions of knowledge. As some wise folks over the millennia have stated in various forms:

- ”The trouble with most folks isn’t so much their ignorance. It’s know’n so many things that ain’t so.” 19th century humorist Josh Billings

- “To know that you do not know is the best. To pretend to know when you do not know is a disease.” Lao-Tzu

- “It ain’t what you know that hurts you. It’s what you do know that ain’t so.” Will Rogers

I’m sure Mark Twain, Winston Churchill, and Disraeli had a version of the same quote.