Develop Products Right!

Design for Supportability

Leading companies evaluate customer experience and support requirements at the design stage to deliver maximum customer value. Do your R&D engineers accept the need for “Design for Supportability”?

During new product development, R&D engineers need to consider a wide range of often-conflicting requirements, including product features, cost, quality and manufactureability. Therefore, it is not surprising that support requirements are often neglected. However, support is an essential factor for achieving customer satisfaction in many industries, and so ensuring that products are easy and economical to support is a priority. Customer support managers know this but often have problems in convincing their R&D colleagues. This article looks at the issues involved in achieving Design for Supportability — the full evaluation of support requirements at the design stage.

Product managers and R&D engineers have a wide range of requirements to consider at the design stage. Typically, these include product features, cost, quality, and manufacturability. Since R&D resources are always limited and fast time-to-market is essential, it is not surprising that customer support is often forgotten during new product development (NPD). However, neglecting support concerns at the design stage is a missed opportunity because ease of support is essential to customer satisfaction in many markets. In addition, support can be a major source of revenue and sustainable competitive advantage. Therefore, it is important that both R&D engineers and product managers fully understand:

In many companies, manufacturing initiatives have led R&D to think beyond their immediate domain of responsibility-or, to use the popular term, think “outside the box”. For example, concurrent engineering is now common practice and this dictates that manufacturing processes should be developed simultaneously with the design of the product. However, this “box of thinking” ends with product shipment, whereas DFS requires R&D to extend their thinking to cover the lifetime use of the product.

Recognition of the importance of support has grown over the years. Support used to be considered as just service and repair, a backwater not worthy of management attention. However, attitudes are now changing for three reasons:

In many markets, support plays a key role in achieving customer satisfaction, and strongly influences repeat purchasing behavior. For example, a key reason why automobile owners do not remain loyal to a brand is because they have received poor after-sales service from dealers.

Customer support is a key source of revenue. In addition, it can be very profitable area-with margins exceeding those made on the products themselves. A McKinsey study concluded that “in most industrial companies, the after-sales business accounts for 10 to 20 percent of revenues and a much larger portion of total contribution margin” [1].

New technologies have changed many aspects of support. Today’s products are more reliable, and this has reduced the relative importance of maintenance and repair. On the other hand, the complexity of equipment has often increased, particularly if it is software-based. This means that aspects of support such as user training and telephone support are now fundamental to many business models. Consequently, designers need to think how support can be simplified because of the costs involved. For example, support costs in the software industry are typically 5-10% of revenues (not to mention the costs customers incur themselves in support product usage).

Many leading companies gain a competitive advantage from support [2]. For example, the Caterpillar Corporation’s support of their earth-moving equipment is legendary-guaranteed delivery of spare parts anywhere in the world within 48 hours and machines that can be repaired quickly and economically. (For more details of their approach to “negative downtime”-predictive software that prevents failures-see [3].)

Another example is EMC, the leader in data storage. This company places such a high emphasis on giving excellent customer support that it has decided to offer only one level of service contract. Only offering one level of service — and the company aims for this to be premium quality — goes against the standard marketing doctrine of defining a tiered set of service contracts. In fact, EMC’s whole service organization is structured as an “investment center”, with the sole mission of bonding customers to the company for future hardware purchases. Consequently, EMC’s service organization offers innovative approaches, such as an extensive “phone home” capability built into their systems to detect problems before a hard failure [4].

A third example is VendorC. This is a pseudonym for a market-leading company that designs, manufactures, sells and supports complex vending machines. Vending companies buy large numbers of machines to provide self-service sales of a wide range of goods, some of high value. Modern vending machines — also known as vending terminals — are a complex mix of mechanical, electronic, security and display technologies and a model can cost in the region of $15,000.

Due to the large number of mechanical components and their high levels of usage, regular maintenance and repair is required. Vending terminals can now be linked via modems to a central computer, which remotely monitors performance, sales activity and stock levels in chains of vending machines. Using modem links, VendorC offer full goods management to their customers i.e. ensuring that machines are both efficiently maintained and replenished with sales goods in a timely fashion.

This incremental service is a new and important source of revenue for VendorC, and it arose from their consideration of support needs at the design stage. VendorC’s management assigns significant resources to support as it generates 35% of sales at margins of typically 25%. For VendorC, customer support is the source of competitive advantage-so much so that the company does not want to attract their competitors’ attention and consequently wants to remain anonymous.

Product design influences both the degree of support necessary and the way it can be delivered. For example, decisions taken at the design stage affect product reliability and consequently the level of maintenance required. Similarly, modular design can reduce repair costs, and troubleshooting is made easier by good diagnostics. In addition to repair and maintenance, design also influences user training and product upgradability. For example, remote support avoids the need for costly on-site visits and on-board features can significantly reduce the amount of training that users require on complex products. However, the impact of design upon support requirements typically does not receive enough attention during new product development.

Four factors inhibit companies from developing products with high supportability i.e. products which are easy and efficient to support. These are:

Several studies have found that support is neglected during NPD. A survey conducted by one of the authors, showed that many high-technology companies do not consider support until well into the product development cycle-on average after two-thirds of the development cycle has passed [5]. At this stage, it is too late to ensure high supportability of product, because most of the design decisions have already been made. With fast time-to-market the norm, it is essential for support to be considered right from the start.

In most cases R&D engineers do not have sufficient knowledge of the issues facing field support personnel. However, field support engineers who know the issues first hand are seldom consulted on the suitability of proposed designs. Research in the US has revealed that field personnel are only “occasionally involved in new product work” [6]. Many companies make big mistakes because they do not use the knowledge base of their customer support organizations. For example, the authors are familiar with a company that developed a new product line based on the architecture from a previous product. This was despite the fact that there was a whole body of evidence from the repair depot that this architecture had led to frequent failures in the past, which were extremely difficult to fix.

A recent survey by one of the authors has found that customer support’s influence early in the product development cycle has increased over the past few years, but it is still not the norm [7]. Leading companies such as NCR, HP, GE and AT&T recognize the importance of panels of field experts reviewing the supportability of new designs [8]. All aspects of product support should be considered, whereas research has shown that many companies limit their evaluation at the design stage to repair and maintenance issues only, thus omitting many other key aspects [4]. The evaluation of all aspects of product support at the design stage is called Design for Supportability.

If companies are not careful, decisions taken to lower production costs may increase support costs. An example is memory boards for products. The goal of minimum material costs often leads production personnel to choose non-reprogramable memory. However, when products need to be field upgraded, this can increase costs-as whole memory boards need to be exchanged. The authors know of two major international companies where this was the case-a few dollars were saved in production but the costs of field upgrades were enormous when the companies had to upgrade their installed base (to solve software problems). It is essential that both R&D and production engineers consider lifetime cost-of-ownership. This is because higher development and production costs may lead to lower lifetime costs!

Product management at CompanyX, a maker of desktop software tools, decided to lower the costs of documentation shipped with the product. Since their sophisticated software products only retail for about $200, the cost of printing the documentation exceeded the cost of manufacturing the software medium and other packaging. So product management set a goal to cut the documentation costs in half for the next product release. The support organization, which at the time was not part of the “core team” that made these product decisions, only found out about this decision when asked to review the documentation (one task where support is typically consulted). When they saw the abridged documentation, support was flabbergasted because they knew that the information omitted would lead to a huge increase in calls to technical support. Since these calls cost the company on average $20-25 apiece, the documentation cost saving would be more than offset by increased support costs. They built a business case showing the trade-off and suggested ways to embed more of the documentation information into the product through templates and on-line error messages. Thus, they helped meet the goal of reducing documentation cost without increasing support costs.

A major reason why Design for Supportability is neglected is that R&D engineers tend to give product features a higher priority, as these may be more interesting to develop. Product marketing may push new product features and “bells and whistles” over functions that could make products easier to support since they feel new features allow selling the product to a broader customer base.

In addition, product managers may forget the importance of support and the associated revenues. This is particularly common at companies where product-development entities are a separate organization from the field organization, which supports released products. In this case, the field organization’s revenues are separate from the manufacturing division’s and so there is little financial motivation for the product groups to develop products which are easier and more profitable to support. Implementing DFS may require significant investments by R&D for which no return will be seen in the product-development entity’s bottom line. However, leading companies evaluate the return on investment from product features and compare this to how investments in supportability can give returns over the working lifetime of the product. In essence, supportability is treated as a feature.

Some companies such as Rank Xerox, Hewlett-Packard and VendorC excel at DFS. They achieve this through a clear understanding of customer needs and an evaluation of product support early in the design cycle.

Rank Xerox was one of the first companies to fully evaluate support requirements at the design stage. They are particularly strong at surveying customers’ support needs-something that many companies miss when they conduct market research that focuses on product features alone. Rank-Xerox sets goals for all aspects of support at the design stage; an example is their analysis of the access time to various modules of a photocopier. They found that more money was saved by considering field repair times than from speeding up assembly time in production. Why? The reason was simple. A copier is assembled once in the factory but repaired in the field (including disassembly and re-assembly) many times during its working lifetime by field engineers. Rank-Xerox now has a company design goal that the field access time to any component/module in a photocopier must be less than five minutes.

VendorC, the vending machine company excels at Design for Supportability. Their new products typically require 18 months development, and the team working on NPD includes R&D, product management, manufacturing, suppliers and customer support specialists from the start. At the design stage an analysis is made of the RASUI of products-the reliability; availability; serviceability; usability; and installability. In each of these five categories design goals are set and the Quality Department has responsibility for ensuring that RASUI goals are met during NPD. VendorC’s focus on customer support has enabled them to gain a significant competitive advantage and the company has achieved good returns on its investments in DFS.

One of the world’s largest software companies improved DFS by creating the role of “Supportability Engineer”. This engineer is responsible to both communicate the lessons learned by support personnel to the product designers and to develop new data collection tools. The software company also made product support a cost center and instituted Activity Based Costing in its accounting system. As a result, product designers quickly became interested in improved supportability features that drove down the product’s bottom-line costs (costs which product managers now also saw on their P&Ls, which affected their personal bonuses).

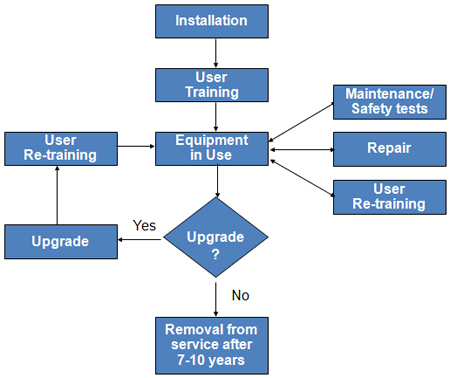

Hewlett-Packard has always had a strong reputation for good product support and has focused on DFS since the early 1990s. Two key elements in their approach to DFS are their lifetime costs model and their financial reporting [7]. To identify the issues and costs involved with support, a lifetime model is used and Diagram 1 shows an example for a medical electronics product. The diagram illustrates the “events” during the working lifetime of a product, from installation, through use and maintenance, to removal from service. By determining the frequency of each event and the associated costs, better decisions can be taken about the potential returns on investments in making support more efficient. For example, installation normally only takes place once but a product may require several upgrades over its lifetime.

Diagram 1:

Hewlett-Packard use a lifetime costs model to analyze both the frequency and associated costs of all support “events” (such as installation or upgrading).

Therefore, the lifetime model ensures that all aspects of support are considered at the design stage and not just repair and maintenance. As mentioned earlier, supportability issues may have to “compete” for resources during NPD with product features or manufacturability. Thus, a clear understanding of the cost implications of support is essential and the lifetime cost model helps. However, Hewlett-Packard has gone further and changed their financial reporting so that product divisions (which design and manufacture products) see financial returns on DFS investments. Previously, field support revenues had been reported separately and so the motivation in the product divisions to invest in DFS was low (because these investments would make the field support organization more efficient but not increase factory margins). Following the change in financial reporting, better decisions have been made during NPD.

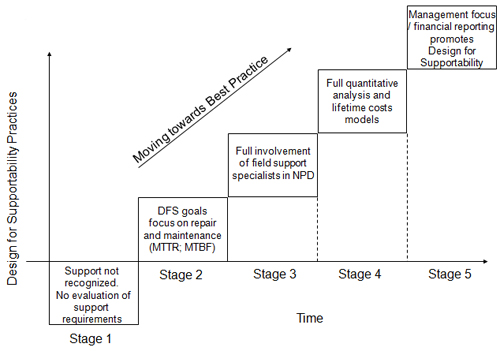

Extensive research by the authors in a range of industries shows that companies typically go through five stages in the progression towards full Design for Supportability, as illustrated by Diagram 2. Companies at Stage 1 do not recognize the potential of support business. Consequently, they do not evaluate support at the design stage. Symptomatic of companies at Stage 1 is the customer support organization having a low status and field support complaining about product designs. Poor product design means higher repair costs and can lead to dissatisfied customers. Therefore, failing to consider product support at the design stage often has a negative business impact, as indicated by the position of Stage 1 on the diagram.

Diagram 2:

The Five Stages, which companies typically move through, until they achieve effective Design for Supportability.

Some leading companies have reached Stage 5, which is characterized by all of the issues considered at At Stage 2, companies consider reliability and repair times at the design stage and typically set quantitative goals for product reliability (mean-time-between-failures, MTBF) and ease-of-repair (mean-time-to-repair, MTTR). However, broader aspects of support are not considered at the design stage. Further progression leads to Stage 3, where companies involve panels of field engineers in NPD reviews. However, often field engineers’ suggestions cannot be implemented because reviews come too late in the development cycle. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate all aspects of support at the design stage i.e. installation times; fault diagnosis times; field access times; repair times/costs, user training times; upgrade times; etc. Integrating this into NPD is difficult, and it often takes companies a long time to reach Stage 4. Companies at Stage 4 set quantitative goals during the design phase for all aspects of support. These goals push R&D engineers to develop new products, which are easier and more profitable to support than previous products. Cost models are used to guide the decisions about trade-offs between features, manufacturability and supportability.

Stage 4 with two important additions. Firstly, financial reporting mechanisms are used to ensure that return on DFS investment is clearly visible to management. Secondly, and fundamentally, companies that reach Stage 5 have management teams, which fully recognize the importance of support to their business models and to their product’s value propositions. Consequently they devote sufficient resources to analyzing a product’s cost structure over its entire life cycle. Achieving this change in attitude is something many companies find hard and few companies have reached Stage 5. However, the competitive advantage resulting from DFS can be stark.

An example of the advantage of evaluating repair issues at the design stage comes from the car industry. During product design Volkswagen evaluates the probability of each part of a car being damaged in an accident and the associated repair costs. This is important because car insurance companies closely monitor the costs of repairing accident damage and use this information in the calculation of which insurance category applies to a particular model of car. Hence, repair costs have a direct influence on the cost of insurance, which itself has a major impact on product sales especially to young purchasers. The cost of insuring the latest model of the Golf has been reduced by full two insurance classes-through bolt-on panels instead of welded ones, and bumpers molded in three separate parts (to allow partial replacement). The lower insurance costs have given VW a competitive edge and forced competitors to make expensive changes in the design of their products and production lines.

Moving from Stage 1 to Stage 5 is a change that cannot happen overnight. It is a considerable journey for a support organization to increase its influence over the product design stage. Here are some of the keys to a successful transition:

Again, don’t expect overnight success. You will be challenging engrained business processes. Look for small successes, market them well, and move a little deeper into the designers’ den, without losing track of the goal. And remember, if you get products developed right through Design for Supportability, the return on investment is clear-more profitable support revenues and a competitive advantage.

Have you experienced problems in trying to achieve DFS, or do you have a success story? In either case the authors would like to hear from you.

Get more information about a major research report on best practices in Design for Supportability.

~ ~ ~

Knecht, T., Leszinski, R. and Weber, F.A. “Making Profits After the Sale”. The McKinsey Quarterly 1993, No. 4, pp. -86.

Goffin, K. “Gaining a Competitive Advantage from Support: Five Case Studies”. European Services Industry, 1(4), December 1994, pp. , 5-7.

Fites, D. V. “Make Your Dealers Your Partners”. Harvard Business Review, March-April 1996, pp. -51.

Rao, J. and Reitz, W., “EMC: Rewriting Customer Service Rules”, Babson College Working Paper, 1999.

Goffin, K. “Evaluating Customer Support during New Product Development – An Exploratory Study”. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15(1), January 1998, pp. -56.

Page, A.L. “Assessing New Product development Practices and Performance: Establishing Crucial Norms”. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 10(4), September 1993, pp. -290.

Van Bennekom, F. and Goffin, K., “Using Customer Support’s Knowledge Base To Enhance New Product Development,” Service Operations Management Association Conf. Proceedings, 1999.

Hull, D.L. and Cox, J.F. “The Field Service Function in the Electronics Industry: Providing a Link between Customers and Production/ Marketing”. International Journal of Production Economics, 37(1), November 1994, pp. -126.

~ ~ ~

Originally printed in The Professional Journal of AFSMI, August 2000

Written with Dr. Keith Goffin, PhD. Dr. Goffin is Professor of Innovation Management at Cranfield School of Management in the UK. For fourteen years he worked for the Hewlett-Packard Medical Products Group: on new product development, managing customer support groups, and as a marketing manager. He was also largely responsible for developing HP’s “Design for Supportability” program. In 1995, Keith joined the teaching faculty of Cranfield and his research interests are all in the field of innovation. He has published over forty articles in management journals and this is his third article in AFSM’s Professional Journal.