Net Promoter Score — Summary & Controversy

Summary: The Net Promoter Score® is widely adopted and wildly controversial. What exactly is NPS and what are the various areas of controversy for using this survey question as a customer insight metric? This article provides a summary of the NPS concept and the critical concerns.

~ ~ ~

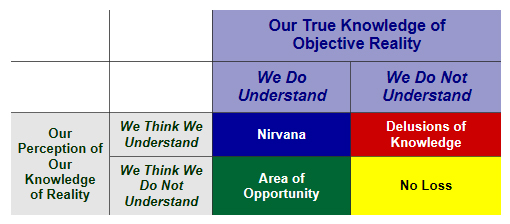

In an earlier article, I discussed the need for having confidence that the customer insight metrics we use in our operation are valid indicators of underlying customer sentiment. Here I am specifically focusing on those summary metrics we capture in our feedback surveys. This article will focus its attention on the Net Promoter Score®.

The Net Promoter Score (NPS) has achieved a near other-worldly place in the arena of customer metrics. It is certainly the most hyped measurement seen in decades, yet the fundamental measurement has been used for decades. What is new is the claim of the metric to predicting customer behavior along with the particular statistical technique applied to the data. After examining these points, we’ll turn to issues with NPS as the indicator of customer sentiment.

What is NPS?

NPS is quite simply the self-reported measurement of a respondent’s likelihood to recommend a product or service to others. That’s it.

How likely is it that you would recommend [Company X] to a friend or colleague?

This is not a new concept. The recommendation question has been asked for decades in customer satisfaction research. I can recall hearing a keynote speaker at a conference 25 years ago present the big three of summary customer measurements: customer satisfaction, likelihood of future purchase, and likelihood of recommendation. But now the claim is that the response to this question provides unique insight to a company’s forward profitability.

How Do We Know It’s Hyped?

Why do I say that NPS is hyped? Just look and listen to how NPS is used in business discussions. Companies aren’t doing customer satisfaction or customer relationship surveys; they’re now doing “NPS surveys.” Some companies actually have job titles that include “NPS.” Frankly, this is every consultant’s dream to have their trade-marked phrase become part of the business lexicon. So, call me jealous.

While many companies have never heard of NPS, you will find companies that have drunk the Kool Aid lock, stock and barrel. In these companies, NPS has achieved a mystical aura and everyone tracks the company’s NPS on a near real-time basis. NPS measurements are pushed down in the company, even to an individual level, across all departments. It’s even used to measure service provided internally within a company. This can border on obsession. One company with which I’m familiar recognized the obsession was obstructing focus on core business practices and scaled back its use of NPS.

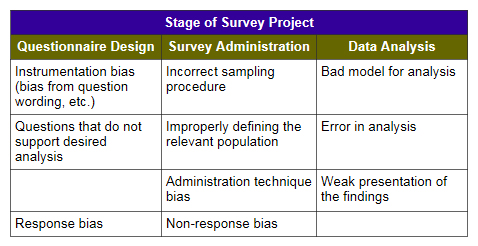

I have seen many company surveys where questions are posed predominantly on 5-, 6-, 7-, or 10-point scales, but when it comes to the NPS question, Reichheld’s 0-to-10, 11-point scale is somehow sacrosanct. Sadly, I know that part of the reason is to allow comparisons of the company’s NPS against published NPS data. Any professional surveyor will tell you that such comparisons are highly dubious, given the differences in survey instruments and administration methods. People seem to treat NPS scores as if they’re accounting data following standardized practices. They’re not.

The Background for the NPS Claims

The Net Promoter Score first came to prominence with an article by Fred Reichheld, a Bain consultant, in the December 2003 Harvard Business Review, “The One Number You Need to Grow.” The article opens with Reichheld recounting a conference talk by the CEO of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Andy Taylor. He talked about his company’s “way to measure and manage customer loyalty without the complexity of traditional customer surveys.” Enterprise used a two-question survey instrument; the two questions were:

- What was the quality of their rental experience?

- Would they rent again from Enterprise?

This approach was simple and quick, and we can infer from other comments in the article the survey process had a high response rate, though none is stated. Enterprise also ranked its branch offices solely using the percentage of customers who rated their experience using the highest rating option. Why this approach? Encouraging branches to satisfy customers to the point where they would give top ratings was a “key driver of profitable growth” since those people had a high likelihood of repeat business and of recommendations.

Reichheld, thus intrigued, pursued a research agenda to see if this experience could be generalized across industries. The first stage of this research was to identify what survey question correlated best with a person’s future purchase behavior. In most cases — but not all — the willingness-to-recommend question was the best predictor. Reichheld conjectures that the more tangible question of making a recommendation resonated better with respondents than the more abstract questions about a company deserving a customer’s loyalty.

The second research stage was to validate the recommendation question as a predictor of company growth. Through some unspecified statistical procedure, they decided to group the responses on a 1-to-10 scale into three groups. 1-to-6 respondents were “detractors,” 7-to-8 respondents were “passively satisfied,” and 9-to-10 respondents were “promoters.” (Note that later the scale was changed to a 0-to-10 scale. The addition of the zero supposedly clearly identifies which end of the scale is positive.)

Satmetrix — Reichheld sits on their Board of Directors — then administered the recommendation survey to thousands of people from public lists and compared the responses for various companies against the companies’ three-year growth rates.

The study concluded “that a single survey question can, in fact, serve as a useful predictor of growth.” The question was: “willingness to recommend a product or service to someone else.” The scores on this question “correlated directly with differences in growth rates among competitors.” (emphasis added) This “evangelic customer loyalty is clearly one of the most important drivers of growth.”

That’s the research basis for NPS as a customer insight metric. In comparison to the Customer Effort Score, this is a very robust research program. But Reichheld added another element to the conversation beyond just setting the recommendation question upon the pinnacle of what surveyors call “attitudinal outcome” survey questions. He also added a new statistic: net scoring.

The Net Scoring Statistic

Net scoring adds a certain mystical aura to NPS. We’re not just measuring a survey score; we’re taking a net score. A statistics professor of mine talked about the “Ooo Factor.” If a client would utter “Ooo” when a statistic was presented, then it had cachet. Net scoring has that Ooo Factor. It sounds so sophisticated. (In my workshops, I include the statisticians’ term for averages: “measures of central tendency.” Talk about an Ooo Factor!)

Well, a net score is a just a statistic to describe a data set. The mean (or arithmetic average) is also a statistic to describe a data set. The mean and the net score of a data set are very likely to tell the same story.

Quite simply, net scoring takes the percentage of data at the top end of the distribution, in this case respondents’ survey scores, and subtracts from it the percentage of respondents who gave us scores at the low end. The top end and bottom end scores are frequently called “top box” and “bottom box” scores, respectively. The technique can be applied to any survey question that has ordinal data properties, not just the “promotion” question — but that would dilute its aura.

The earliest reference I have found for this net scoring statistic is an online article by Rajan Sambandam and George Hausser in 1998, though they recommend multiplying the bottom box score by a factor of two or three to give it more impact.

% 9s + 10s)

– (% 1s to 6s)

————————

Net Promoter Score

The goal of any statistic is to summarize a data set into one or two numbers that we can comprehend, digest, and apply to some decision. Reichheld advocates the net scoring approach to provide visibility to the bottom end of the distribution. Improving the views of those who are unhappy is the best way to drive overall improvement, and Reichheld wanted NPS to be used by the front line managers to improve operational performance.

However, net scoring actually throws away data distinctions, which the mean does not. A survey score of 1 has the same weight as a 6, a 9 the same as a 10. Aren’t those distinctions important? Aren’t the behavioral characteristics of a customer scoring a 1 likely to be different from a customer scoring a 6 or a 9 different from a 10? While the simplicity of the approach is a virtue, some valuable information can be lost through its simplicity.

Regardless, the idea that we’re calculating a net score whose tracking will lead to promotion of our business certainly has grabbed the attention of senior managers. And managers love a “number” to run their businesses.

The Issues With NPS

But maybe the hype about NPS is justified. And maybe not. Here are some of the concerns that have been raised with NPS.

Cannot reproduce the results. The most telling issue with NPS is that researchers have tried unsuccessfully to replicate the findings that Reichheld and Satmetrix developed as the core argument for the role of NPS in companies. This plays to the point of the earlier article about the need for reliable research.

Keiningham et al. in the Journal of Marketing, July 2007 present research using available data sources, including the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) since the data Reichheld used was not available. As this was published in an academic journal, it went through a peer review process which Reichheld’s research did not. The authors did not find that the recommendation question was superior in predicting company future profitability. In fact, the satisfaction question was superior. The authors conclude:

The clear implication is that managers have adopted the Net Promoter metric for tracking growth on the basis of the belief that solid science underpins the findings and that it is superior to other metrics. However, our research suggests that such presumptions are erroneous. The consequences are the potential misallocation of resources as a function of erroneous strategies guided by Net Promoter on firm performance, company value, and shareholder wealth.

Additionally, Morgan and Rego published research in Marketing Science (2006), examining “The Value of Different Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty Metrics in Predicting Business Performance.” They found:

Our results indicate that average satisfaction scores have the greatest value in predicting future business performance and that Top 2 Box satisfaction scores also have good predictive value. We also find that while repurchase likelihood and proportion of customers complaining have some predictive value depending on the specific dimension of business performance, metrics based on recommendation intentions (net promoters) and behavior (average number of recommendations) have little or no predictive value. Our results clearly indicate that recent prescriptions to focus customer feedback systems and metrics solely on customers’ recommendation intentions and behaviors are misguided.

If the research by Reichheld et al. cannot be replicated by others, how sound is the blind devotion to this measure?

Is NPS for relationship or transactional surveys — or both? Reichheld says that the metric is best for annual, high-level relationship surveys. Yet, he promotes using NPS to identify at-risk customers and driving the results to the front line to fix the customer relationships. This sounds more like something that should be done in transactional surveys. This seeming contradiction leads to the next issue.

The question is potentially ambiguous. Many companies pose the NPS question in relationship surveys with no wording adjustments. But consider how differently you might react to these two questions on a transactional survey after the closure of an interaction with a company:

- How likely is it that you would recommend [Company X] to a friend or colleague?

- Based on your most recent experience, how likely is it that you would recommend [Company X] to a friend or colleague?

In the first version, respondents may use different benchmarks for their answer. Some would base their response on their most recent experience, while others would use their overall experience in some undefined time period. How would you interpret the results if different benchmarks are used? Quite simply, you cannot. The definition of an invalid question is where respondents can have drastically different interpretations of the question. If using the net promoter question on a relationship survey, the ambiguity must be removed.

Where’s the promotion? While called Net Promoter Score, the question asks the likelihood of making a recommendation. The behavioral difference between recommending and promoting is cavernous. Promotion is active. Recommendation is in response to a request for information. Shouldn’t it be called Net Recommend Score™ (NRS)? But that doesn’t have the same Ooo Factor, does it?

What about so-called Detractors? The bottom end of the scale is typically anchored as “highly unlikely to recommend.” If you’re highly unlikely to recommend, does that make you a detractor, someone who is actively going to give bad word of mouth?

Not applicable to all situations. In many situations people cannot make recommendations. Ask any government employee if they can make product recommendations. They cannot. They would be fired for fear of kickback schemes. Reichheld recognized this shortcoming in his 2003 article where he noted that NPS works better for the consumer product world than in business-to-business situations. Yet, that critical distinction has been missed.

The solution is to phrase the question as a hypothetical.

If you were able to make recommendations, how likely is it that you would recommend [Company X] to a friend or colleague?

Some companies have made this adjustment, but now our question’s syntax is getting complicated.

Creates a focus on getting word-of-mouth recommendations. Did the research show that getting recommendations led to higher company profitability? No. It showed a correlation between the likelihood to recommend a company with its future profitability. While we certainly want good word of mouth, it should be the byproduct of improved operations and product value. NPS has made the focus on getting recommendations.

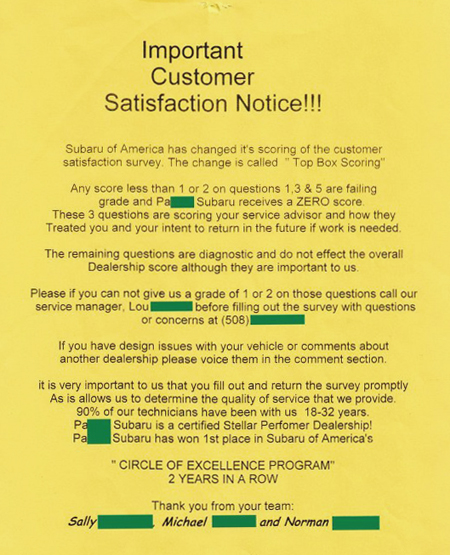

It’s become a measurement tool, not operational tool. As mentioned, Reichheld viewed NPS as a means to drive changes in the front line, especially in addressing customer concerns. But NPS has become a performance measurement tool. This can lead to perverse behavior that can actually hide problems. Organization Behavior 101 teaches us that people will improve a performance appraisal measure — whatever it takes.

We increasingly see a business transaction conclude with the agent telling us that we’ll be getting a survey and if we can’t give them top scores to call someone before filling out the survey. I have personally experienced some truly over-the-top examples of this. On one hand, you might say, “Great, this is getting front line attention.” But on the other hand this may also mean that a symptom is being treated while the existence of the core problem is hidden from senior management.

Net scoring threshold effects. Net scoring is susceptible to big threshold effects. While a change from 10 to 9 has no effect on the net score, a change from 9 to 8 does. Small changes in a survey instrument design or administration that have nothing to do with customers’ underlying feelings could lead to these shifts, amplified by the net score. Research that I’ll be publishing shortly shows how survey mode — phone vs. web-form — impacts survey scores, and the net scoring approach amplifies the differences.

Cross-company comparisons. As mentioned earlier, many people think that scores on specific survey questions can be compared across companies without consideration for differences in the wording of the survey question, scale lengths, or the placement of the survey question within the broader survey. Such comparisons are highly dubious at best, but with NPS as an industry best practice metric means the comparison is done – blind to the issues. The best, most legitimate benchmark is against your own company’s previous survey scores.

More than one number you need to know. The myopic fascination with NPS, along with the title of the seminal article, “The One Number You Need to Grow,” has led people to think you only need a one-question survey, devoid of any complementary diagnostic questions or research. Reichheld himself doesn’t recommend this; however, he buried this information in his article in a side bar in parentheses. What people have heard is “The One Number You Need to Know.” Not true.

~ ~ ~

Measuring whether customers would recommend your company and its products and services is a valuable indicator of customer feelings. But does this one score deserve the exalted place it has achieved in the business world? How likely would I be to recommend NPS as the only customer insight metric? I’d rate it as a 2 – not very likely.

Note: NPS and Net Promoter Score are trademarks of Satmetrix Systems, Inc., Bain & Company, and Fred Reichheld.

Your first reaction probably is that the writer’s English skills are woeful — and that’s being kind. With my professorial red pen, I count 16 editing corrections in one page. Three people had their names at the bottom of the page. (I blanked them out for privacy reasons.) Didn’t they proofread this? Maybe they did, which would be really sad. If I were the owner of this dealership, I would be embarrassed. The sloppiness sends a message about the dealer as a whole. It’s a window into the concern for quality at the dealership. One can only hope they are better, more careful mechanics than writers!

Your first reaction probably is that the writer’s English skills are woeful — and that’s being kind. With my professorial red pen, I count 16 editing corrections in one page. Three people had their names at the bottom of the page. (I blanked them out for privacy reasons.) Didn’t they proofread this? Maybe they did, which would be really sad. If I were the owner of this dealership, I would be embarrassed. The sloppiness sends a message about the dealer as a whole. It’s a window into the concern for quality at the dealership. One can only hope they are better, more careful mechanics than writers!

The help desk was true to its name, but Ralston-Purina’s interaction with the customer is not purely passive. A few days later, I received a phone call whose purpose was to conduct a survey on behalf of Ralston-Purina. The interviewer asked not only whether the information request was fulfilled and the agent was courteous, but also whether my experiences with the customer service desk would make me more or less likely to buy Ralston-Purina products in future. In other words, this telephone survey was trying to assess the affect of the help desk upon my loyalty to the company and its products.

The help desk was true to its name, but Ralston-Purina’s interaction with the customer is not purely passive. A few days later, I received a phone call whose purpose was to conduct a survey on behalf of Ralston-Purina. The interviewer asked not only whether the information request was fulfilled and the agent was courteous, but also whether my experiences with the customer service desk would make me more or less likely to buy Ralston-Purina products in future. In other words, this telephone survey was trying to assess the affect of the help desk upon my loyalty to the company and its products.